About Frederick M. Nicholas

Fred Nicholas was born May 30, 1920 in Brooklyn, New York. His father was Ben Nicholas who was the first member of his family born in the United States. Ben was a laundry supply salesman and worked for Washine National Sands. His mother was Rose Nechols, a distant cousin of Ben. They were married June 15, 1919 in the Bronx, New York.

Fred grew up in Brooklyn, New York and Cedarhurst, Long Island. The Nicholas family migrated to Los Angeles in 1934 where Fred attended John Burroughs Junior High, graduating in 1935; Los Angeles High School, graduating in 1938; and USC, graduating in 1947. Fred passed away June 28, 2025 at the age of 105.

Fred Nicholas, age 5, the Bronx, New York.

Fred Nicholas, age 3.

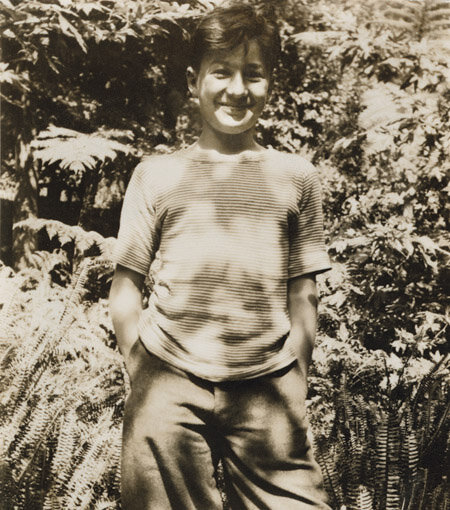

Fred Nicholas, age 9, 1929.

Fred Nicholas, age 12, 1932.

Fred and his sister Helen, New Orleans, March 1934.

(left to right) Aunt Penny Nechols, mother Rose, sister Helen, father Ben and Fred Nicholas.

Fred Nicholas, age 16, at home, 5161 San Vicente Blvd, Los Angeles.

Fred Nicholas, 5161 San Vicente Blvd, Los Angeles, 1938.

Fred Nicholas, Los Angeles, 1940.

Fred at 5161 San Vicente Blvd, 1940.

Fred and Eleanore at Fred's law school graduation, 1952.

Fred on his 101st birthday, May 30, 2021.

Frederick M. Nicholas, 1920-2025: An Appreciation

On May 30, 2025, Frederick M. Nicholas celebrated his 105th birthday. Few others reach this milestone, but even fewer could ever claim a century-plus life as extraordinary as Fred’s – distinguished not only by its far-ranging experiences, but even rarer, by the compassion, social concern, and cultural responsibility that Fred demonstrated time and again. War hero, lawyer, businessman, benefactor and philanthropist, civic leader, adored family man – Nicholas lived large. His friends were legion, for good reason.

The forces that shape courage, selflessness, and commitment – hallmarks of a life of greatness -- are mysterious. There’s no way to predict whether the first-hand ordeals of wartime, for example, will produce heroism or cowardice. Repeated heroism characterized Nicholas’s military service in World War II, and bravery and a commitment to the larger good were the foundations underlying his subsequent achievements.

In 1941, America called. It needed him, and he went. As an Army officer, he pursued Rommel across North Africa and participated in the invasion of Sicily, driving the Germans out of Italy. He then headed to the Philippines in the Pacific campaign. At his 105th birthday, Nicholas became the oldest surviving World War II veteran, and, with a Bronze Star and Purple Heart, one of the most decorated.

Perhaps the most formative episode in his Army career, however, came during his service at the Japanese-American internment camp in the Tanforan Race Track near San Francisco. Appalled by the suffering at hand, at great peril the 21-year-old Nicholas smuggled the internees food, other essentials, and belongings from their homes. The experience left Fred with an indelible moral compass, teaching him that the individual acting out of a sense of justice could make a profound difference in the lives of others. His lifelong dedication to social and civic activism was born and took root.

After his wartime service, Fred worked as a journalist covering the longshoremen’s strikes in Hawaii, and then he earned a law degree. In Los Angeles he became a successful attorney specializing in real estate law and development, but he quickly realized that he could apply his private-sector expertise to the public sector as well. Inspired by Ralph Nader, who urged lawyers to give back to society, Fred founded— in a one-room office, with his own funding— Public Counsel, providing free legal services to abandoned children, homeless families, veterans, senior citizens, consumer fraud victims, and nonprofit organizations serving low-income communities. Today, with a 140-member staff and thousands of volunteers, Public Counsel is the nation’s largest resource of its kind.

Characteristically, Nicholas didn’t name Public Counsel after himself, preferring to act quietly without attracting attention. As with everything he undertook, he believed in simply doing the right thing.

Fred’s selflessness flowered again in the 1980s, when Downtown Los Angeles, like the Army decades before, called. His combined legal and developer skills were precisely what was needed to help overcome a prolonged stasis in the City’s cultural arena. He promptly volunteered his expertise, and over the next twenty years he masterfully led the creation of two landmark projects, The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), and the Walt Disney Concert Hall. Both brought Los Angeles to the national and international vanguard of contemporary architecture and culture.

At MOCA, Nicholas exercised his customary diplomatic skills to deftly negotiate the shoals of competing egos among the founding trustees. Together with director Richard Koshalek, Nicholas made the fledgling museum a reality. He led the Board during the glory years of assembling major collections and building the endowment. Under Fred’s aegis, MoCA quickly became one of the world’s most acclaimed museums of contemporary art.

During MOCA’s ascendency, Fred also became a renowned patron of contemporary art and artists far and wide, eventually acquiring major works by Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, Ed Ruscha, Ad Reinhardt, Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Donald Judd, and Sam Francis, among others. Lasting friendships with the artists blossomed as well (especially with Francis). Long before others, Fred also collected superb examples of pre-Columbian and African art.

MOCA’s success than set the stage for Nicholas’s crowning cultural achievement in Los Angeles: his leadership throughout the design and development of the Walt Disney Concert Hall, the greatest architectural masterpiece in the City’s history. As the Hall’s initial Committee chair beginning in 1987, and operating largely behind the scenes (again, pro bono), Nicholas adroitly assembled working groups drawn from various constituents to raise the necessary funds and formulate the building process. Most importantly, his architecture selection committee, uniting the heads of LA’s top museums and architecture schools, awarded the project to Frank Gehry, who had hitherto been bypassed for major commissions in his own hometown. As much as anything, Fred’s advocacy enabled Gehry to invent the magnificent edifice that now crowns the corner of Grand Avenue and First Street.

Never during his eight-year tenure at Disney Hall did Nicholas ask to have his name placed on any of the building’s exterior or interior spaces. The finished masterpiece -- and the resulting leap in the international stature of music in Los Angeles -- were his reward. With this achievement, Fred joined the generation of great civic leaders who established Los Angeles’s standing as a world cultural capital.

Fred then proceeded to deploy his skills in other cities, with similar acclaim. He developed the $900 million Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center, Washington D.C.’s largest building after the Pentagon. And he returned to the Tanforan Race Track in San Francisco, where he built a shopping center and, most movingly, dedicated a memorial to the Japanese Americans confined there when the site was an internment camp. As ever, he deftly negotiated the labyrinthine details inherent to these massive projects, orchestrating personalities, positions, power, and funds to reach the desired outcomes.

Perhaps Fred’s finest achievement, however, was the one most prized by those in his private sphere: adored family man. Throughout his life, Fred exemplified the roles of patriarch, husband, father, confidante, supporter, and bestower of limitless affection to his family. His love was returned by all in his closest circle, including the many friends fortunate to be admitted to it as well.

Throughout his extraordinary life, Fred wrought the best possible outcomes in everything he undertook. Everyone he encountered benefited from his indomitable spirit and grace. Immeasurably more than most, Fred made the world a better place.

July 2025